The only Washington-bred

to score

the

Longacres Derby/

Longacres Mile double

by Kimberly French

![]() t was the year the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, commencing what would be termed as the “Space Race;” the year the Shippingport Atomic Power Station, which was the first commercial nuclear power plant in the United States, opened its doors; the year Little Rock, Arkansas, initiated the desegregation of its school system, as well as the year the first civil rights legislation was passed since the Reconstruction period after the Civil War; and of course, it was the inauguration year of the Eisenhower Doctrine.

t was the year the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, commencing what would be termed as the “Space Race;” the year the Shippingport Atomic Power Station, which was the first commercial nuclear power plant in the United States, opened its doors; the year Little Rock, Arkansas, initiated the desegregation of its school system, as well as the year the first civil rights legislation was passed since the Reconstruction period after the Civil War; and of course, it was the inauguration year of the Eisenhower Doctrine.

Naturally, all these events were acknowledged, avidly followed and ruminated upon by David and Phyllis Brazier of Seattle, and while admittedly they shaped the course of national and world history, none of these occurrences had the personal impact and effect as the birth of their broodmare Watch the Show’s second foal.

The Braziers, who had settled in Seattle in 1921 after leaving their native England behind, had married shortly after David satisfied his contract with the Canadian Army in 1919. They built the Brazier Construction Company that constructed residential and commercial structures and eventually erected Seattle’s Opera House in 1963.

Though the Braziers were not immediately enamored with the sport of racing horses, during the 1930s their affection for the business began to grow. It wasn’t until around 1952, however, that they purchased several horses in conjunction with George Matheny and E. A. “Sleepy” Armstrong. The partnership continued for several years until David bought the others out and decided to go out on his own.

The Show Begins

The Braziers’ early horses weren’t exactly collecting championship trophies, but they were picking up enough checks to cover the bills, and around 1954, David thought the time was ripe to expand his holdings into the breeding arena. He procured Watch the Show, a daughter of Watchimtick and Showum, from noted Washington horseman Cecil Jolly for $1,000 and bred her to top stallion Succession. The result was a nice-looking or “eye-catching” filly, as Russell Brown wrote in July of 1964, which the couple named Phylembra after Phyllis. A few years later, a repeat visit by Watch the Show to Succession produced Playfair Mile Handicap winner Sixpenny Lane, who also placed in ten other stakes.

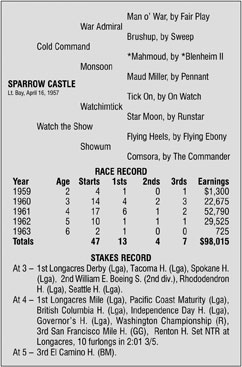

Watch the Show was next bred to the new stud Cold Command – a $206,225 winning son of Triple Crown winner War Admiral – and when that foal, a bay colt, was dropped in 1957, it forever altered the Braziers’ lives and took them on a journey of incredible joy.

The Seattle couple decided to name the newborn Sparrow Castle, after the first home they had resided in shortly after their marriage, which possessed a spectacular view of the celebrated white chalk cliffs of Dover and of the equally famous English Channel.

As a juvenile, Sparrow Castle was transported to Turf Paradise in Arizona to start his racing career under the care of conditioner Wayne Branch.

“Branch didn’t think much of him,” Brazier had recalled. “He thought he was a silly horse and had no sense.”

When the colt debuted, he didn’t do much and seemed to verify Branch’s low opinion of his ability, but in his second trip to the gate, which was carded as the third race on the May 1, 1959, Turf Paradise program, Sparrow Castle captured a $1,000 maiden claiming contest over 11 rivals by 5 1/2 lengths in a hand ride in a time of :59 1/5, nearly tying the track record for that distance established by five-year-old Bettyanbull, which had stood since that February.

As a freshman, Sparrow Castle raced four times, with the aforementioned victory and a third place finish on his résumé. After that season, he was sent north, where he took up residence in 2008 Washington Hall of Fame inductee Glen Williams’ shedrow.

In 1960, Sparrow Castle’s three-year-old year, the colt matured into what the Braziers always thought he was. In his first start at Bay Meadows he cut the pace and tripped the timer first in 1:10 3/5 for six furlongs. He then journied to Longacres where he went on to collect victories in the Longacres Derby, the Spokane Handicap and the Tacoma Handicap, otherwise known as the Washington Triple Crown, before finishing second in both the Rhododendron Handicap and William E. Boeing Stakes and third in the Seattle Handicap against older rivals.

In the 6 1/2-furlong Tacoma Handicap on July 3, Sparrow Castle just outlasted Royal Balladier to win by a scant neck. In the one mile Spokane Handicap on July 27, the colt simply rolled to another victory over Royal Balladier, defeating that rival by five lengths, and in the Longacres Derby, he came from way off the pace to defeat runner-up Jet Tiger by another neck, as well as Royal Balladier, Jewelsmith, Aryess and Minnegrode, in the mile and an eighth contest.

For his efforts, which included four triumphs, two second place finishes and three thirds in 14 races and purse earnings of $22,675, Sparrow Castle was elected as the Evergreen State’s champion three-year-old and horse of the year.

More Accolades

Although his 1960 campaign certainly was outstanding, the colt still had much to show his burgeoning group of fans in 1961, which included the Braziers’ son David Jr. and his wife Lillian.

The four-year-old won in succession the Governor’s Handicap, the Independence Day Handicap, the Washington Championship, the British Columbia Handicap, a thrilling 26th edition of the Longacres Mile and the Pacific Coast Maturity.

He also finished third in the San Francisco Mile Handicap and the Renton Handicap that season.

“The Sparrow,” as he was affectionately dubbed, won more stakes events (five) and banked more greenbacks at Longacres ($44,290) than any other horse during one year of racing in the state’s history. At the time, his career bank account of $76,665 was the fifth highest among the leading Washington-bred money winners of all time and many members of the press called him the best horse ever produced in Washington.

For the second year in a row, the Brazier homebred was honored as the Washington horse of the year. He finished the season with a record of 17-6-1-2 and a photograph of his nose defeat of Dusky Damion in the Longacres Mile graced the January 1962 edition of The Washington Horse.

The Curtain Falls

However, 1962 wasn’t as kind to the Braziers and their stable star. After discovering the stallion had developed osselets, he was “fired” and given some time off to roam the fields and recover. During that year he faced the starter on ten occasions with one victory, one second and one third place finish – in the El Camino Handicap – while managing to earn $20,525.

In 1963, Phyllis passed away and The Sparrow was put back in training for a comeback, but after his ankles began to plague him, he was taken to Washington State University where a surgical procedure was performed in hopes to rectify his sore joints.

Transferred to the barn of Joe Boyce, Sparrow Castle returned to the racetrack, but the wear and tear of racing had taken its toll on the horse’s legs. He left the gate twice with one win and a paycheck amounting to $725 before David retired him from racing.

Even though he had hoped for the best, Brazier had prepared for the worst.

“If he doesn’t work out, he’ll make a good stallion someday,” he had told Russell Brown in 1964.

During his race career, Sparrow Castle contested 47 races with 13 wins, four seconds and seven third place finishes. He earned $98,015, is the only horse to win both the Longacres Derby and the Longacres Mile, and his nine stakes victories at Longacres stood as a record until overhauled by 2011 Hall of Fame inductee Firesweeper in 1987.

Sparrow Castle either established or tied track records at Longacres from distances of 6 1/2 furlongs to a mile and a quarter and competed at other tracks, such as Santa Anita and Bay Meadows, against other top class horses of the era.

For example, he was fourth in the 1961 Santa Anita Handicap to Physician and came home in front of Grey Eagle, Mr. Consistency, Headmaster, Prove It, Spy Flight, First Balcony, New Policy and British Roman.

“I wasn’t around at that time, but his old grooms used to tell stories about what a character he was,” remembered David Brazier III. “He lifted a farrier or someone doing work on him off the ground by his shirt. He had a tremendous personality.”

A Second Career

After his days at the racetrack had ended The Sparrow stood at Pineridge, Glen Williams’ farm in Spokane for the fee of $500 his first season. He sired seven crops with a total of 28 foals. Twenty-two of these made it into the gate, 12 won and one was a stakes winner.

His top performer and sole stakes winner was the filly Reminiscent (1967) from his second crop. The bay filly out of Bay Cloud, by *Oceanus II, compiled a career record of 6-7-8 from 48 starts with a $39,286 bank account. Her stakes win came in a division of the Hilltop Handicap at Longacres in 1970.

Like many stallions during their second career, he failed to replicate himself, but what Sparrow Castle accomplished while running and the elation he provided for his connections hasn’t elapsed, even after nearly five decades.

“Sparrow Castle became a hero and a horse we all remember from those days, Emerald Downs President Ron Crockett said at the 2009 Hall of Fame induction ceremony. I became part of the woodwork with David and Lillian and moved to Magnolia. There was a group of guys David Jr. spent a lot of time with. There was the meat market man, the barber, John Johnson, the pharmacist, Jacobson the clothier, Bob Cop in the construction business and they were all pals. They always golfed together and I became very close to them and very much a friend. He was the only horse to win the Longacres Derby and the Longacres Mile, I believe six stakes victories and on and on. Those days were the glory days and that horse just kept winning. It was a wonderful time for all of us, ‘The Magnolia Mob,’ so to speak, that backed that horse and it was just a big time in my memory of racing.”

Kentucky resident Kimberly French is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in Thoroughbred, Standardbred and Quarter Horse publications. She also freelances as a production assistant for ESPN’s horse racing broadcasts.

Click here for a complete list of all the Washington Hall of Fame inductees.

WASHINGTON THOROUGHBRED, March 2012, page 22