A polished reinsman

by Susan van Dyke

“Follow James and wear diamonds, bet against him and sleep in Howard Street flophouses . . . Five-a-day James . . . Polished reinsman . . . He might even defy the law of gravity, if he set his mind toward it . . . Follow James . . . A boy with a good pair of hands and a lot of judgment . . . One of the best race riders in America . . . A firecracker with a delayed action fuse . . . Sensational.”

![]() ll of these colorful accolades

come from late 1930s’ newspaper clippings commending the riding prowess of

Basil B. James, the 2005 jockey inductee into the Washington Racing Hall of

Fame.

ll of these colorful accolades

come from late 1930s’ newspaper clippings commending the riding prowess of

Basil B. James, the 2005 jockey inductee into the Washington Racing Hall of

Fame.

From Bush Tracks to Big City Lights

He was born in Loveland, CO, on May 18, 1920 (and not

1918, nor in Sunnyside as many of the record books would have you believe) to

Lee and Gladys (Maxwell) James. The third of three children, Basil, his sister

Shirley and brother Harold were sent to live with their grandparents, Bert and

Lucinda James, after their mother died of appendicitis. Basil was just six

months old. His dad “was a great rider of bucking horses at Pendleton

roundup and other rodeos . . .”

Grandfather

Bert, the major influence in his life, was a migrant farmer who trained a few

horses – that doubled as plow horses – at the local bush tracks. The

family would spend the summer months in Washington, Montana and Oregon, and

winter in Arizona. The James’ family members were all short, and Basil

would grow to only 5’ 1” in his stocking feet.

Basil would always remember his grandfather’s sage

advice, “Sonny, always remember that the horse is your best friend. He

does not talk, and he may not be very intelligent, but he is flesh and bone.

The horses feels, like you and I. Always be kind to him, and you will never

regret it.”

Basil had only a sixth grade

education, which was not uncommon for those growing up in the Depression era.

“I had been riding since I was old enough to

walk. In fact, I think my dad and granddad put me in the saddle before they put

me on my feet,” said James in a 1937 interview in California.

His first unofficial win came either aboard his

grandfather’s Sineta in Helena, MT, or astride Bert’s Cibble at

Salem. Reports are conflicting, but in either case he was just 14.

“Well, they put me up on Cibble and I was so

scared – it was a five-eights mile race on a half-mile track. Did I tell

you I was scared? Well, that doesn’t describe my feeling. My knees where

shaking so that I guess old Cibble got the idea that I was a greenhorn and

chose to get me off to a good start. We broke well in a five-horse field race

and I simply hung on,” James would later tell reporter George T. Davis.

“Before I knew it we were out in front, and I realized it wasn’t so

different from galloping around the exercise track. I can tell you I was the

happiest kid in the world when we hit the wire first and I moved into the

winner’s circle. Gee, when I rode another winner the next day – two

wins out of three races – I wondered how long that racket had been going

on. I saw visions of Earl Sande and Tod Sloan [Sande, a three-time leading

rider in the 1920s turned successful trainer, would later make use of the young

James’ talent; Ted Sloan made his hefty reputation as a rider at the turn

of the 20th century] rolled into one.”

From

there, James went to the newly reopened Playfair Race Course in the summer of

1935 and rode his first “official” winner at that Spokane track

aboard Infanta on September 1, 1935. A year later, he lost his apprenticeship

while riding at Washington Park in Illinois. While the 1936 (covering the year

1935) American Racing Manual lists the then 15-year-old James as riding

“freelance” in 1936 and 1937, his contract was held by H. H.

Cross’s Tranquility Farm. By 1938 he was employed by noted Seattle

airplane manufacturer William E. Boeing, who raced a very high class stable. He

soon would buy his contract from Boeing for $7,000. In later years, C.V.

Whitney would hold his contract and he would also ride for the likes of Fred

Astaire, Calumet Farm, Jock Whitney and Mrs. Damon Runyon.

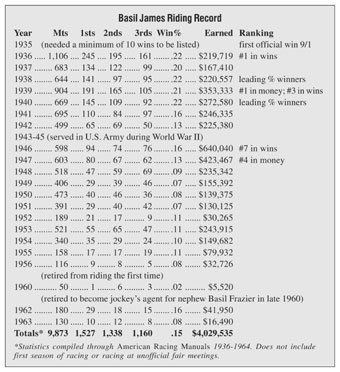

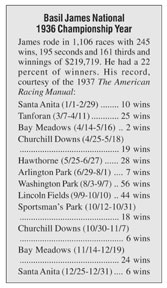

America’s Champion Rider of 1936

James’ first stakes win came aboard A.C.T. Stock

Farm’s three-year-old Indian Broom in the April 11, 1936, $10,000

Marchbank Handicap at Tanforan against older runners – and in world record

time. Top Row, who had won the second running of the Santa Anita Handicap in

his previous start, went off as favorite in the nine furlong stakes. But,

“Jockey B. James made perfect disposition of the speed of Indian Broom. He

took his mount to the front at once, opened up a good lead under slight

restraint, and kept enough in his mount that Indian Broom could widen his

margin steadily through the stretch. He won off by himself, seven lengths in

front of Top Row,” with 1935 Santa Anita Handicap winner *Azucar running

third. Indian Broom’s 1:47 3/5 mark knocked three-fifths a second off the

previous world mark. Indian Broom would later run third to Bold Venture in the

Kentucky Derby, though not with James aboard.

On

August 1, James rode Calumet Farm’s Sun Teddy to a head victory in the

$10,000 Arlington Handicap. The 2:02 was the fastest 10 furlongs run to that

point in time in 1936.

James would earn his third

stakes victory aboard Jaipur (a son of *War Cry, not the one who memorably vied

with Ridan) at Bay Meadows on Thanksgiving Day. Just a few weeks prior to that

second stakes win, James was suspended until the end of the meet at Churchill

Downs, when on November 2, his mount Surveyor moved over on Biff in the stretch

and was disqualified from first to last. James, who was in a close battle with

Frank Chojnacki for the leading national riding title, actually lost little

time, as the Kentucky meeting ended just five days later.

James would win the national title as a 16-year-old

apprentice (see box) with 245 wins at 12 different tracks in California,

Kentucky and Illinois. Johnny Longden finished in second place with 212

victories, three more than Frank Chojnacki. “James’ meteoric spurt

during September and part of October at Lincoln Fields where he averaged almost

two winners per day, and during the last weeks of October at Sportsman’s

Park, where he actually passed Chojnacki, won him the championship. When both

riders resumed hostilities at Bay Meadows in November and early December,

Chojnacki was still within easy striking distance of the lead, but James’

brilliant form continued . . . and James drew farther away with each passing

day.”

1937

James made

the first of his five appearances in the Kentucky Derby in 1937, when he

finished seventh to War Admiral while aboard J. W. Parrish’s Dellor in a

field of 20. He won three stakes races that season, but only one, the San

Pasqual Handicap with Special Agent at Santa Anita – where he was leading

rider for the meet – was on the west coast. The other two were in

Maryland.

1938

The year

1938 would start out on a less than auspicious note, when on January 12 the

young rider was suspended for the remainder of the Santa Anita meet. The

California Racing Board later extended the suspension to 90 days. James

received the severe penalty for “grabbing Herbert Litzenberger during the

running of the seventh race.” The time out for the infraction would more

than likely cost him the mount on Stagehand, who James regularly galloped

during morning workouts for trainer Earle Sande. Stagehand would score a major

upset over Seabiscuit in that year’s edition of the Santa Anita Handicap

and later be named the nation’s champion three-year-old colt of 1938. It

was not the first, nor would it be the last, major suspension James would be

handed.

In a newspaper interview by Bob Herbert

that year, the young James was asked what was important in race riding.

“It’s all in knowing how to rate your horses - and knowing how much

he’s got left for the finish,” he said. “The most important part

of a race is the start. If you can’t keep your horse straight in the

stall, so that he can get away well, and if you can’t keep him out of

trouble going around that first turn, you haven’t much of a chance.

That’s where most races are won and lost – right on that first

turn,” he remarked. James would later add, “. . . but you got to have

a good horse,” to the equation.

Though at the

time he was noted to be a strong whip rider, James preferred giving a horse a

hand ride to the finish. “When you whip a horse, you turn his head loose,

and when you turn a tired horse’s head loose you can’t tell

what’s going to happen.”

James would hit

the New York circuit for the first time in 1938. Later that year, he would be

astride Boeing’s top two-year-old Porter’s Mite when the son of The

Porter won the $3,000 Champage Stakes over the 6 1/2 furlong Widener course

after having “skittered over the straight six furlongs in 1:14 2/5,

four-fifths of a second faster than the world record set by Menow in last

year’s Futurity.” In their next outing together, James and

Porter’s Mite took the $25,000 Futurity at Belmont by a nose over Eight

Thirty.

Winnie O’Connor, who had been

America’s leading rider in 1901, hailed the riding ability of James after

seeing him ride at Jamaica Race Track. “I’ve been watching that kid

and he’s a natural if ever I’ve seen one,” said O’Connor.

“Perfect seat and a nice pair of hands on a horse. Horses seem to run for

him whether on the head end or off the pace, because he tries to help

them.”

James led the nation with 22 percent

winners from starters in 1938. Sixty-six of those winners came during an

incredible run at the Tanforan fall meet. “His riding at Tanforan has been

practically flawless,” wrote turf writer Oscar Otis. On at least two days

during the 25-day meet, James rode five winners. “James’ amazing

percentage of 41 percent is considered a new high for any single meeting in

turf history.”

According to a newspaper

clipping of the time there were three reasons for James’ incredible

success. “He was the best rider at Tanforan . . . He has a clever agent,

one ‘Bones’ LaBoyne, who is also something of a handicapper. Bones

goes over the entries and selects the best mounts for James. Basil does the

rest.” The other factor was the 40-odd head of Thoroughbreds in

James’ contract employer Boeing’s stable, where there were “no

cheap ones.”

1939

James would

have a banner year in 1939, winning 10 stakes and leading all jockeys in the

country with $353,333 in earnings. He would also finish third in number of

winning mounts with 191, behind only Don Meade and Johnny Longden.

The former Sunnyside boy would be aboard Townsend B.

Martin’s Cravat when that runner became the 113th horse to hit the

$100,000 mark in North America and set a new track record in the $20,000

Brooklyn Handicap. Cravat and James were once again partnered for the $5,000

Jockey Club Gold Cup, in which “Cravat came out smartly at the finish, and

won by a length and a half” over *Isolater. James was also aboard John Hay

Whitney’s Heather Broom when the Earl Sande-trained runner won the $5,000

Blue Grass Stakes at Keeneland and the Saranac Handicap later that summer at

Saratoga. In the Kentucky race, after being the “distant trailer,”

“Basil James kept Heather Broom on the rail, which most riders at the

meeting consistently avoided, and saved ground around the turn.” He then

sent Heather Broom “up fast” to catch Third Degree in the last 100

yards and win by a length.

James would also be the

jockey of choice for Falaise Stable’s good mare Red Eye when she easily

won the 69th running of the $5,000 Ladies Handicap (the oldest stakes

exclusively for fillies or mares in America) and the Gazelle Stakes.

Columnist Jack Guenther would later write of James,

“As a stretch rider he has few – if any – equals.”

1940

Among

James’ 11 major stakes triumphs in 1940 was a victory aboard Foxcatcher

Farms’ Fairy Chant in the $5,000 Gazelle Stakes. In a torrential rain

storm, she and James won the 1 1/16 miles stakes by five lengths. The daughter

of Chance Shot would later be named the nation’s champion three-year-old

filly and champion older filly or mare in 1941 as well. Other notable wins came

with Can’t Wait in the Butler Handicap, Good Turn in the Sanford Stakes,

High Breeze in the Juvenile Stakes at Belmont, Parasang in the Saranac Handicap

and astride that season’s Kentucky Derby winner, Gallahadion, in the San

Vicente Handicap.

James was also aboard Whichcee

for that famous running of the Santa Anita Handicap in which Seabiscuit finally

got up for an emotional victory after running second twice in the $100,000

event. Whichcee, the second betting choice, ran third, beaten two lengths, in

the 10 furlong stakes behind the entrymates of Seabiscuit and *Kayak II. James

would lodge “a claim of foul against the winner, saying Seabiscuit had cut

him off at the sixteenth pole, but the protest was not allowed.” If the

claim had been allowed, rules of the day would have made Whichcee the winner,

as entrymates were considered as one.

1941

James began

the year with a six length win in the $10,000 Santa Susanna Stakes at Santa

Anita astride Mrs. Vera S. Bragg’s Cute Trick on January 18. The following

day, James gave a performance which would go down in California racing lore.

“Basil James turned in a bareback

performance. He was moving up with Roman General, the four-to-five chance [in a

$1,500 claimer], in the stretch when the saddle slipped and the jockey lost

both stirrups. Leaving the saddle to its own devices, James sat down and rode

and won by a neck.” Joe Hernandez got on the public address system and

called James’ unusual victory, “one of the great feats in American

turf history.”

He would later be aboard C.V.

Whitney’s good three-year-old colt Parasang for two 1941 stakes victories.

The first was in the Carter Handicap at Aqueduct, where the pair set a new

track record of 1:23 for seven furlongs while running over a track labeled

“muddy.” Later that summer, James and Parasang won the Wilson Stakes

at Saratoga.

In what James would later declare one

of his most exciting moments in racing, the young rider would drive hard with

Louis Tufuano’s Market Wise to defeat recent Triple Crown winner Whirlaway

by a nose in the $10,000 Jockey Club Gold Cup. The two three-year-old colts

exchanged the lead several times in the stretch with Wood Memorial winner

Market Wise prevailing in a new American record time of 3:30 4/5 for the

two-mile marathon.

Alsab

Alsab has

gone down in turf history as one of the greatest bargains of all time.

Purchased as a yearling for a mere $700 by Albert Sabath – who named the

runner after himself – Alsab would earn $350,015.

Alsab ran a strenuous 22 times as a juvenile in 1942,

winning 15 races, including 11 stakes and was named champion two-year-old. He

then almost immediately began his three-year-old campaign in Florida.

Noted author/illustrator C. W. Anderson would write,

“No three-year-old in years had been asked for so much and had given so

generously.” He poignantly added, “If a little less had been asked,

there would have been more to give.”

As it

was, Alsab went to the post 23 times at three. James was the rider of choice

for all three of the son of Good Goods efforts in the Triple Crown. Just prior

to the Derby, James had ridden Alsab in the Chesapeake Stakes and finished

second by a length to Colchis over a cuppy track.

On May 2, 1942, 15 three-year-olds faced the starter in

the 68th Kentucky Derby with favoritism going to the Greentree Stable

entrymates of Shut Out and Devil Diver. Lukewarm second choices, both at

$5.10-to-one, went to the non-coupled colts Alsab and Requested. James had been

confident going into the race that Alsab would wear the roses. According to the

Derby chart, “Alsab, taken to the outside after a half-mile, started up

after three-quarters and closed resolutely to head Valdina Orphan. But in the

end it was Shut Out who won the race by 2 1/4 lengths, with Alsab second.

The 67th running of racing’s second jewel, run

only one week after the Derby on May 9, saw 10 runners making the call to post

for 1 3/16 miles race. In his ninth start of the year, Alsab finally got his

first win. But oh, the press mutterings that were heard before and after

Alsab’s long overdue win were colorful and opinionated, to say the very

least.

“On the night before the Preakness

Stakes, a frequently heard jest in Baltimore was, ‘Let’s run out to

the track; they might work Alsab again.’ . . . seldom has there been such

practically universal criticism of a horse’s conditioning as there was of

Alsab’s. Some of it got in print, some was hardly printable. Trainer

Augustus Swenke got off pretty lightly, most of it going to Albert Sabath and

his friends – notably Al Jolson – who were often referred

collectively as ‘Alsab’s trainers.’ Sports writers were most

vociferate about it all, but many a horseman shook his head and vowed –

off the record, of course – that he had never seen a good horse so badly

managed.” Nowhere was James vilified in the proceedings.

The report continued, “On the following afternoon,

Alsab swept down the Pimlico homestretch with a smothering rush, drew clear at

the end, and won what was, by 1 1/5 seconds, the fastest Preakness at the

present distance.” The track record, only two ticks faster at 1:56 3/5,

was set by Seabiscuit when that runner vaulted to victory over War Admiral in

the famous Pimlico Special (match race) of 1938.

In the race itself, “Alsab, which was knocked

against Valdina Orphan [who later became T9O Ranches’ first stallion] at

the start and had got none the best of it, was next to last the first time

past. . .” Requested soon took the lead from Apache, and “Alsab still

had but one horse beaten” as they straightened in the backstretch. As

Requested drew clear in the final turn, “Alsab moved at last. He picked up

two more horses before he reached the turn. Coming to the furlong pole Alsab

had reached full stride, and he rapidly cut down the field ahead of him . . . a

sixteenth from the finish it was a question of how much would Alsab win by, for

he was running much faster than anything in the field.” The official

margin was one length with Requested and Sun Again dead-heating for second.

James would say after the victory, “I knew I

was home at the quarter pole. He was a great horse today.”

“Coming from second to last, and superlatively

ridden by Basil James, Alsab drive past the field to win going away . .

.,” wrote Thoroughbred Record editor William Robertson.

In between the Preakness and the Belmont Stakes, Alsab

and James went to Belmont Park for the mile Withers Stakes. In a stakes report

of the race, it was commented: “After the Kentucky Derby at 1 1/4 miles,

and the Preakness at 1 3/16, and with the 1 1/2 mile Belmont Stakes next in

prospect, the one mile Withers Stakes ($15,000 added, three-year-olds) at

Belmont Park makes no kind of sense as far as training routine is concerned,

since horses already up to 10 furlongs, and getting ready for 12, are asked to

drop back to eight.” Nevertheless, the Swenke-trained Alsab won the race

by 2 1/2 lengths.

Just one week later, Alsab, bet

down as the .40-to-one favorite, went forward with six others for the Belmont

Stakes. Leading up to the race much of the criticism had died down due to

Alsab’s sterling performances in the Preakness and Withers. “Alsab

was about to become a super-horse again, and when someone asked Basil James

about his mount’s chance, he answered, ‘You mean how far we’ll

win, don’t you?’”

It was a

different story the Monday after the race, the Associated Press frankly stated

that Alsab “had been overtrained, and matters were back where they

started.” As for the Belmont, Eddie Arcaro, aboard Shut Out, was told to

“wait on Alsab and then move with him.” By the mile post, Shut Out

held the lead by a half-length over Alsab and that’s how they stayed, with

Shut Out defeating the game Alsab by two lengths.

Alsab would race 11 more times at three, including

seven more wins (all in stakes) and gain his second year end champion title. At

four, he won one of five starts and was unplaced in one try at five. By the

time of his retirement to stud, the hickory Alsab’s record stood at

25-11-5 from 51 starts.

The Rest of 1942

Besides his Preakness victory that May, James was also

the winning rider aboard Market Wise in “America’s premier handicap

– [when] tradition, class of horses, and severity of test considered

– in the $30,000 Suburban Handicap on May 30.” It marked the richest

running in the history of the 56-year-old event. Attending the Suburban that

year was the largest crowd in New York history and they proceeded to

“break the state record for betting on one race and the national record on

betting for one day of sport.” Favoritism in the 10 furlong stakes went to

Calumet Farm’s 129 pound highweight Whirlaway and the fans’ second

choice was Market Wise, with 124 pounds, including James in the irons. James

kept his mount closer to the pace than usual and in the final stretch slipped

Market Wise down on the rail. Before the eighth pole had been passed, Market

Wise held the lead and while “Whirlaway was boiling down the track,

fourth, gaining in every stride,” Market Wise won by two lengths and

“was pulling away from the entire field, including Whirlaway.”

Uncle Sam’s Army

World War II changed the life of many a young American

man, and Basil James was no exception. He was inducted into the U.S. Army on

August 28, 1942 and just a day later, when his former classic mount Alsab was

winning the American Derby, James was taking his second Army physical. A

newspaper clipping of the day written by Harry Grayson said, “Basil James

will miss the winter season, of course, but is happy to ride for Uncle Sam, the

greatest trainer of them all, until victory is achieved.”

Even with his abbreviated year, the New York Turf

Writers’ Association named him the country’s leading rider of 1942.

James was sent to Ft. Robinson, NB, which was the

largest U.S. Army Remount Depot in the 1930s and would process most of the pack

mules used during the Second World War. While there, he “broke horses and

mules for the army, but managed to ride in a few races” at many

“local” fair meets.

“While

stationed at the fort, several former riders got weekend passes and furloughs

to ride at some of the ‘bush tracks’ in the west. Some of the

memorable tracks included Columbus, Mitchell and Harrison, Nebraska; Lusk,

Wyoming; the Bot Stot Stampede in Sheridan, Wyoming and Billings,

Montana,” wrote Hildebrandt.

During the war,

the fort also served as the “army’s primary dog training center and

was a major internment camp for German prisoners of war.” Several top

young riders spent their war years in middle America. Other members of the Ft.

Robinson jockey colony included Louis Hildebrandt, who became a good personal

friend of James and later would win the 1946 Flamingo Stakes aboard Round View;

Ira Hanford, who had won the 1936 Kentucky Derby on Bold Venture; his brother

Carl Hanford, trainer of future great Kelso; Bobby Dotter; and Ed Connolly.

Polo also became a part of their daily routine.

Colonel Carr, the commander of the depot and who was

considered a topnotch horseman, kept the former riders busy and

“safe” at home.

It was during his stay

in Nebraska that James met, courted and married his future wife Grizelle, a

very pretty blonde who worked as a bank teller in a local bank in Crawford. The

couple would later have two daughters, Jacqueline and Charlene.

1946-1955

After

the war, James set up shop in New York. In the meantime, his former agent Bones

LaBoyne had become the agent for Arcaro. There were hard and hurt feelings when

LaBoyne decided to stick with Arcaro, instead of returning to guide James’

career. Arcaro would later add leading money riding titles in 1948, 1950, 1952

and 1955, to those he had already earned in his pre-LaBoyne days in 1940 and

1942.

Among James’ dozen stakes wins in 1946

were six aboard Hirsch Jacob’s $1,500 claiming treasure Stymie, a victory

aboard dancer/actor Fred Astaire’s Triplicate in the $100,000 Hollywood

Gold Cup and a win with Mighty Story in the Discovery Handicap over the great

Assault.

In late July, James had flown in from his

New York base to ride Triplicate, a five-year-old son of Reigh Count, in the

California race after his regular rider Job Jessup had been suspended. James,

who reported after the race, “We got all the breaks,” edged out Louis

B. Mayer’s great mare Honeymoon by a neck in the 10 furlong race. The

final time of 2:00 2/5 equaled the Hollywood Park track record.

James was aboard Stymie through much of his

five-year-old season. The pair won the Edgemere Handicap at Aqueduct, the

Gallant Fox Handicap at Jamaica, the New York and Manhattan Handicaps at

Belmont and the Saratoga Cup and Whitney Stakes at Saratoga. In the August 31

running of $15,000 Saratoga Cup, Stymie became the fourth horse to win the 1

3/4 mile race in a walkover. Stymie won the 45th running of the Manhattan

Handicap over Pavot with that year’s Triple Crown winner Assault

dead-heating with Flareback for third in the $25,000 stakes. Stymie and James

also finished second to Assault, Arcaro up, in the $25,000, winner take all,

Pimlico Special.

In 1947, James ranked fourth in

the nation in monies earned. Among his 80 victories was a win aboard his

gallant partner Stymie in the $25,000 Metropolitan Handicap. Champion distaffer

Gallorette, whose connections were never afraid to run her outside of her sex,

finished third.

In 1948, Pavot, with Arcaro in the

saddle, evened the score on James and Stymie when he defeated him in the

$25,000 Jockey Club Gold Cup. “Basil James, Stymie’s rider, is a

superior reinsman, and possibly no jockey could have avoided the predicament

created by Arcaro’s tactics, which was to make Stymie make the pace.

Arcaro knew that the son of Equestrian disliked the front-running chore, is

also at a disadvantage behind a slow pace.” “Cinderella” Stymie

would eventually retire with 35 wins in 131 starts over seven seasons and the

title of world’s leading money winner ($918,485).

From 1949 until 1955, James would record nine more

stakes wins, including two prominent New York stakes on the good juvenile Ferd

in 1949. His last recorded stakes win came at Pimlico in 1955, when he was

astride Alberta and George Gardiner’s English import *St. Vincent when he

set a new American record in the $25,000 Dixie Handicap at Pimlico.

Retirement from Racing – First, Second and

Third Times

James retired from riding –

the first time – in 1956 and moved back to California where he opened up a

restaurant and bar in Arcadia called Basil James Handicap. In 1959, he and

Grizelle divorced and he went briefly back to riding. He tried training for a

short spell, but found himself “not enough of a well-rounded

horseman” to carve a success in that demanding profession, according to

daughter Jackie Hogan.

Hogan recounted that as a

child, she, her sister and her mother were not allowed to go to the track to

watch him ride. James told them, “It was his job. How he made his living.

If I was a fireman, you wouldn’t be coming to the firehouse.”

“I was raised the child of a famous athlete,”

said Hogan, remembering the heady days in California when people like actor

Mickey Rooney and Buster Wiles would come to the house. “He was a very

unique little man,” she added. “He called a spade a shovel!”

Hogan finally got to see her father ride at age 18

when her visiting Aunt Shirley took her to Santa Anita one day. (In 1969, Hogan

began her career in horse racing, first as a hotwalker and then with a small

vanning company in California and later Washington. She was noted for her

ability to handle rough colts and stallions. At first, she didn’t tell her

father of her racetrack activities, but of course he later found out. When he

did, he cautioned his daughter to “Always conduct yourself as a lady when

on the backside.”)

In the fall of 1960,

James’ nephew and namesake Basil Frazier (son of his sister Shirley and

her husband Don Frazier) was struggling as a jockey after recently losing his

“bug.” Uncle James suggested they go to the east coast, where he

would serve as the young rider’s agent. They first went to Florida for the

winter racing and later up into the mid-Atlantic states. Frazier vividly

remembers the respect the elder horsemen gave his uncle, especially in New

York.

“Greatness exuded off of him. If you

put him in a room with a group of people, they would gravitate towards

him,” remembered Frazier.

Their partnership

ended after the better part of two years and James went to ride at the newly

opened Finger Lakes in 1962. Later he would take his tack to Agua Caliente,

where sometimes the two Basils would compete against each other.

Frazier also remembered his uncle’s sometimes

“dual nature.” He could be somewhat cranky or perverse, though he was

privately immensely proud of his nephew. “When I won the Longacres Mile in

1974 [aboard Times Rush], upon returning to the jock’s room, he was

waiting in my corner. I was expecting something like ‘nice ride,’ but

true to form, he said, ‘Well, that horse made you look pretty good.’

Coming from Uncle Basil, that was high praise indeed.”

Other memories of his uncle were warmed by his

out-in-out generosity. “My dad was a rider also, but never the caliber of

Basil,” Frazier continued. He was relegated to the ‘bushes’ and

it was always a struggle of survival. But one thing you could count on; every

Christmas there would always be gifts from Basil and Grizzelle, and they would

always be something special. As much of a curmudgeon as he could be, he was

always generous with his success. Especially with me. There have been occasions

when someone was angry with me and said something like, ‘You’re just

like your uncle.’ I always took it as high praise.”

Back in Washington

In 1963, Longacres president Joe Gottstein journeyed to

the Mexico track to offer James a position with his organization. The horseman

would be a devoted member of the Longacres family for 30 years.

James served as assistant clocker and as a film race

analyst until Longacres closed in 1992. He was also employed as film analyst at

both Playfair and Yakima Meadows.

According to

Hogan, James maintained his strong work ethic throughout his years at

Longacres, rising early every morning to be at the clocker’s stand by

5:00., home for lunch, and then back at the track by 1:00 p.m. to work as film

analyst. “The racetrack was his life,” said Hogan.

In 1967, James was installed in the Washington State

Sports Hall of Fame. As of today, only two other racing figures are in this

elite group and neither one of them – racetrack and horse owner Joe

Gottstein or breeder Harry Deegan – came from an athletic category.

In 1982, James was diagnosed with oral cancer. He had

radical surgery in March of 1983 and remarkably by May of 1983 was back part to

work part-time at the Renton track. Though his voice box had to be removed and

he had to eat with a straw, “he never missed work,” said Hogan.

When the track wasn’t running, James was an avid

fisherman, and “liked to work with his hands. He was good with wood,”

said his daughter. “He also loved cooking and cookbooks.”

On April 10, 1998, James died in a Des Moines nursing

home at age 77. He had suffered from Alzheimer’s disease the last few

years of his life. His youngest daughter Charlene (Saffaf) died seven years

later in February 2005. Today, he is survived by his daughter, Jackie, of Kent;

her half-brother Basil James, of Seattle; grandchildren Jess James Hogan and

Miranda James; his nephew Basil James and various other nieces and nephews.

Famous turf writer and radio announcer Clem

McCarthy once wrote of Basil James during his riding hey-days: “If you

took a vote among modern-day jockeys and asked them who they’d like to be

built like . . . same size . . . they’d probably tell you, Basil James.

And his is the face of a typical high-class race rider. As to pugnacity,

there’s a bit of the battler in him, and a touch of the diplomat . . .

James knows when to take a desperate chance . . . and when to sit cool and bide

his time. Such a rider is not made, but born . . . and too few of them are

born.”

Special thanks to Jacqueline Hogan and

Basil Frazier for sharing their insights and memories of their famous father

and uncle, respectively.

|

|

|

|

Sources: 1947 Year Book of the Jockey’s Guild; various editions of American Racing Manual; various editions of The Blood-Horse; The History of Thoroughbred Racing, by William Robertson; Riders Up, by Louis Hildebrant; The Smashers, by C. W. Anderson; various issues of The Washington Horse; and many 1930-1940s unaccredited and undated newspaper clippings.

Click here for a complete list of all the Washington Hall of Fame inductees.

WASHINGTON THOROUGHBRED, September 2006, page 610