Enumclaw native led nation’s

trainers

five times during 1950s

by Kimberly French

![]() n May 5, 1955, at about 4:35 p.m.,

Robert Hyatt “Red” McDaniel should have been on top of the

world instead of leaping from the highest span of the San Francisco Bay Bridge.

n May 5, 1955, at about 4:35 p.m.,

Robert Hyatt “Red” McDaniel should have been on top of the

world instead of leaping from the highest span of the San Francisco Bay Bridge.

For the previous five years, the 44-year-old

native of Enumclaw, Washington, had collected more victories than any other

trainer in North America, was the first conditioner to win more than 200 races

in one season and had, just in the previous February, captured one of

America’s richest races at the time, the $100,000 Santa Anita Handicap,

with the Irish-bred *Poona II.

The people closest

to him, including his widow Evelyn, never could determine what drove McDaniel

to take his own life, and no suicide note was ever recovered.

“McDaniel’s suicide stunned California racing

circles, like it must have stunned horse people everywhere,” wrote Ken

Cochranton in the Daily Racing Form the day after McDaniel’s death.

“Scores of friends had chatted with him earlier in the afternoon and found

him as quiet, retiring and smilingly pleasant as usual. They were dumb-founded

on hearing the report of his self-destruction – so much so that that they

believed this tragic report was an error or canard – until grim

confirmation forced its acceptance.”

The Early Years

When McDaniel

was in early teens, he left his parents’ dairy farm to become a jockey. He

rode his first winner in 1926 (age 15) at Willows Park, in Victoria, British

Columbia, and although he enjoyed moderate success, he was never a top rider

like his colleague future (1958) National Racing Hall of Famer Johnny Longden.

After he broke his leg in 1929, McDaniel retired

from the saddle. For the next three years he trained a small stable for

Vancouver, British Columbia, resident George Slater at Agua Caliente in Mexico.

After Slater sold his stable, McDaniel worked as a jockey’s agent and as a

yearling trainer at Rancho San Luis Rey in California. As an agent, his clients

included top rider Noel Richardson, 2002 Hall of Fame inductee Jack Westrope

and Red Pollard of Seabiscuit fame.

McDaniel

returned to training as a full time job in 1938 and maintained a small stable

of mostly cheap claiming horses until the end of World War II. His knowledge of

the condition book began to attract an increasing amount of attention around

1946.

Renowned as a “halter man,” or

someone who primarily races claiming horses, McDaniel was often affectionately

referred to as the “Red Raider,” because of his red hair and frequent

pillaging of everyone else’s barns.

McDaniel

was known for his remarkable ability to make stakes horses from claiming

horses, among his successes were: Stitch Again, who McDaniel claimed for

$5,000, earned $97,000 and was beaten a nose by Olhaverry in the 1947 Santa

Anita Handicap; Blue Reading, a $6,500 acquisition, who collected over

$185,000; and Stranglehold, who bankrolled nearly $275,000 after being claimed

by McDaniel for $7,500.

“McDaniel had an

uncanny ability to ‘improve’ his claims,” noted racing author

and Daily Racing Form columnist Leon Rasmussen told John McEvoy in 1999.

“He also had the rare ability to keep his stock going month in and month

out without them becoming jaded or track-weary. The man was an outstanding

horseman.” This was even though McDaniel was “a firm believer in

constant racing to keep horses in shape,” according to backstretch author

Hap O’Connor.

McDaniel’s 1953 Record-breaking Year

From 1946 to 1949, William Molter, who triumphed in the

1954 Kentucky Derby with Determine and conditioned 1958 Horse of the Year Round

Table, won more races than any other North American trainer and led the

continent in purses earned in 1954, 1956, 1958 and 1959.

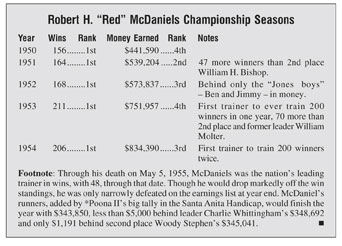

McDaniel wrested the first of five consecutive training

crowns from his close friend and 1960 Hall of Fame inductee when he saddled 156

winners in 1950. Only the legendary Hirsch Jacobs (seven) and H. Guy Bedwell

(six) have won more successive titles.

In 1953, he

became the first trainer in the world to win more than 200 races in one season,

with a final total of 211 victories, and he collected 206 more triumphs the

following year.

According to the 1954 The

American Racing Manual in their write-up “Records of Leading

Trainers,” the Arcadia, California-based trainer “campaigned at six

California courses during 1953, and was the leading trainer at all of them. He

started with 33 wins at Santa Anita, then tacked on, in order, 44 at Tanforan,

22 at Hollywood, 37 at Del Mar, 35 at Golden Gate, 38 at Bay Meadows –

where he first smashed fellow Californian William Molter’s 184 record mark

– then reached and passed the magical 200 figure, and finished the season

at Santa Anita, which opened on December 26, with two winners. McDaniel drew a

blank only at Agua Caliente where he started but a few horses from his vast

public stable.”

“The Shoe” Connection

McDaniel credited William Shoemaker as one of the

reasons for his rise to prominence. McDaniel had been one of the first to

recognize Shoemaker’s ability, and Shoemaker did most of his early riding

on McDaniel horses.

In 1949, “The Shoe”

set a record with 52 wins at the Del Mar meet and became the first apprentice

to win that venue’s riding title. In 1950, the first year he regularly

rode for McDaniel, the 1958 Hall of Fame inductee tied for the most riding wins

with 388. 1951 was the only time during their five-year alliance that he did

not have the most wins or purse money.

When

McDaniel collected a new Del Mar record of 47 victories during one meet in

1954, Shoemaker was in the irons for 42 of them. Nearly five decades later,

“Mac’s” standard has not been bested.

“If there is any formula to my success,”

McDaniel once said, “it has been due to studying the conditions of races,

running my horses where they belong and riding Willie Shoemaker.”

The Hundred Granders

In the

1940s, $100,000 races were a bit of a novelty and only a few tracks had the

means to offer stakes races valued at that magnitude. One of those tracks was

Santa Anita and it was there that McDaniel trainees earned victories in two of

the high-end races.

The first $100,000 success for

the McDaniel stable came via Apple Valley in 1954. The California-bred had

first served note of his class after coming from far off the pace to win the

$15,000 Del Mar Derby. A month into his next season, Apple Valley

“skyrocketed himself into stardom” on January 30 after scoring a

runaway victory in the Santa Anita Maturity, the richest race in the world for

four-year-olds.

After running second in Santa

Anita’s “Big Cap” in 1947, McDaniel brought a four-horse entry

of *Poona II, *Star of the Forest, Ole Travis and James Session – the

largest in stakes history – for the 18th running of the renowned 10

furlong stakes in 1955. The best of these being the Irish-bred *Poona II, a son

of *Tudor Minstrel raced by Herman H. Helbush, a highly successful building

contractor and electronics entrepreneur. *Poona II had begun his four-year-old

campaign on January 15 by impressively winning the $25,000 San Fernando Stakes

in a world record time of 1:40 4/5 for 1 1/16 miles. Among those runners in his

wake were the good Calumet Farm filly Miz Clementine and 1954 Kentucky Derby

winner Determine. Less than a month before the San Fernando, *Poona II, who was

bred by H. H. Aga Khan and Prince Aly Khan, had set a new American record when

taking a 10 furlong allowance race at Santa Anita in 1:47 2/5. The Thoroughbred

Record, which featured *Poona II on the cover of their January 29, 1955, issue,

called the Irish-bred “probably the most talked about horse on the

American turf today . . .”

After *Poona

II’s five-length tally in the San Fernando, his price in the Caliente

future book on the Santa Anita Handicap was cut to two-to-one. Some of his

backers fell off the bandwagon after *Poona II finished a lagging fifth in the

nine furlong San Antonio Handicap, run just three weeks before Santa

Anita’s marquee race, but on February 26, *Poona II, with Shoemaker aboard

for another flawless ride, scored a one length victory in the $104,300 Santa

Anita Handicap before a crowd of 52,500.

Robert

Hebert wrote in the March 5, 1955, issue of The Blood-Horse “there

was genuine admiration in the slight trainer’s voice whenever he mentioned

*Poona II,” who many were wondering if he was as good as fellow import

*Noor, who had been the nemesis of Citation. McDaniel would later openly

declare that *Poona II was the best horse he had ever handled. After the race,

McDaniel and Helbush announced one big objective for their record breaker, the

$65,000 Washington, D.C., International at Laurel in November. Unfortunately,

that was not to be.

Questions Unanswered

Even

though he was well-liked and respected by the majority of his peers, McDaniel

certainly was not immune to malicious gossip. Stories of various illegal (drug)

concoctions from foreign countries frequently traveled throughout the backside,

but no proof of wrong-doing ever surfaced.

“Magic drugs,” Robert L. Baird, a former

jockey and father of 2008 Kentucky Derby partici-pant E. T. Baird, told McEvoy.

“What a bunch of baloney! He was one of the most watched guys in

California racing. And he just kept getting better, winning more races and

improving his stock each year.”

When McDaniel

tumbled to his death, he operated the largest public stable in North America

and was getting $10 per day for each horse in his barns in training fees. His

barns housed 68 head, involved 21 different owners, employed 38 men and

possessed a $125,000 payroll. It cost him more than $600 a day just to maintain

his stable.

Financial concerns, however, were not

an issue. During his career, McDaniel won more than 1,100 races and $4 million

dollars and was in the process of purchasing financial stock in Bay Meadows and

Golden Gate Fields.

He was known on the backside

as a “loner,” but never had a problem handing out money to those in

need.

“Don’t worry about when you can

pay it back,” he was known to say. “You probably need it more than I

do.”

After McDaniel’s shocking suicide,

people close to him began to examine his behavior for clues and admitted there

may have been some warning signs.

Diagnosed with

bleeding stomach ulcers, he was ill throughout nearly all of 1955 and although

McDaniel rarely drank alcohol because it aggravated his condition, his

consumption increased throughout the months preceding his demise.

On the day he died, McDaniel wanted two of his staff

members to deliver a large amount of money he had on his person to his wife

Evelyn at their home in San Mateo. When one of the employees offered to take

McDaniel home after the races so he could perform his transaction privately,

the trainer revealed he did not intend to go home.

Immediately after he hoisted Ralph Neves (1960 National

and 2003 Washington Racing Hall of Fame inductee) into Aptos’ saddle for

the sixth race, McDaniel left the paddock for the final time and guided his

1954 Cadillac to the tallest segment of the Bay Bridge. He parked in the

outside lane, moved resolutely to the railing and roughly 15 minutes after

Aptos won his race, hurled himself over.

1982 Hall

of Fame trainer W.J. “Buddy” Hirsch was one of three men who were

privy to McDaniel’s final moments. Jacobs told Baird he recognized his

fellow horseman, but had no time to derail McDaniel’s plan because he

“moved so fast, we didn’t have a chance.”

His body was recovered by the United States Coast Guard

nearly 25 minutes later and when the police searched his car, they found his

wallet along with $3,000 of uncashed mutual tickets in the front seat. More

than 50 years later, the reason R. H. McDaniel decided to leave this world

remains unidentified. The stress of working from dusk to dawn every day for

almost four decades could have finally taken its toll, but the only one who

knows for certain is the horseman himself, and he’s certainly not talking.

In addition to his widow, McDaniel left two young

children; son, Terry Lee, 5, and daughter, Carole Ann, 4.

“It will never be known what caused McDaniel to

end his own life at a time when, apparently, he had everything to live

for,” wrote Jack Shettlesworth on May 28, 1955. “Somewhere in the

Book which establishes the universal code under which men live in close

society, it says: ‘Judge not lest ye be judged.’ So be it.”

Pennsylvania resident Kimberly French is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in Thoroughbred, Standardbred and Quarter Horse publications. She also freelances as a production assistant for ESPN’s horseracing broadcasts.

Click here for a complete list of all the Washington Hall of Fame inductees.

WASHINGTON THOROUGHBRED, February 2009, page 92